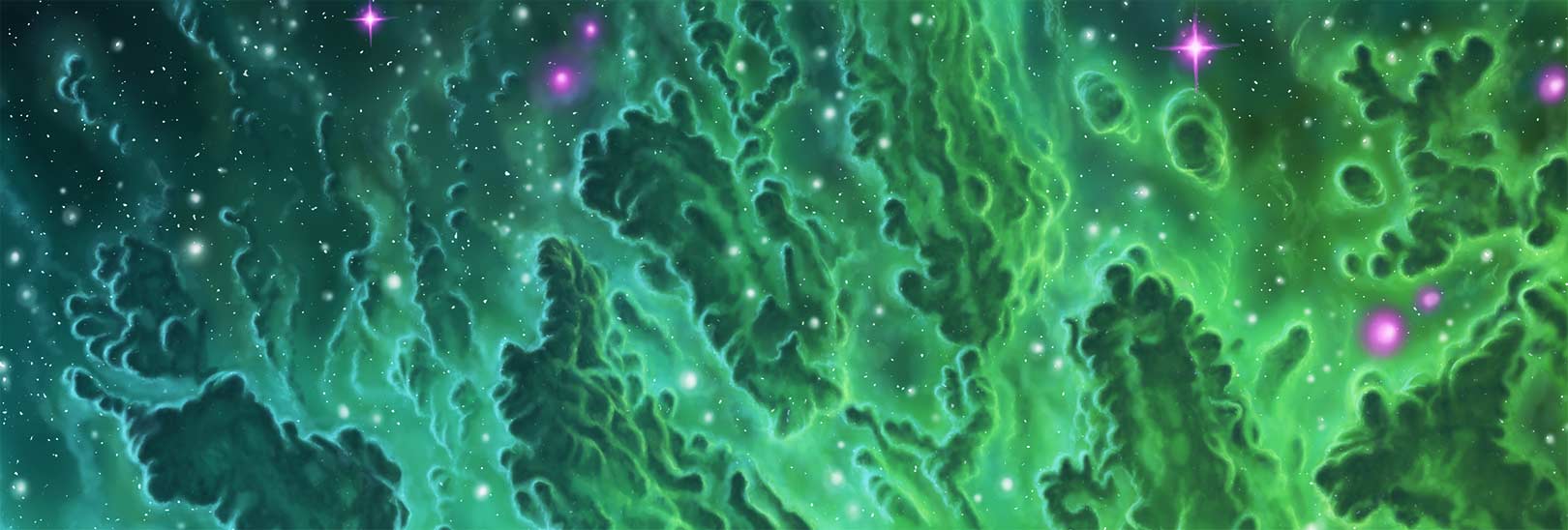

Planet Veteris

A cradle of life in the cosmos

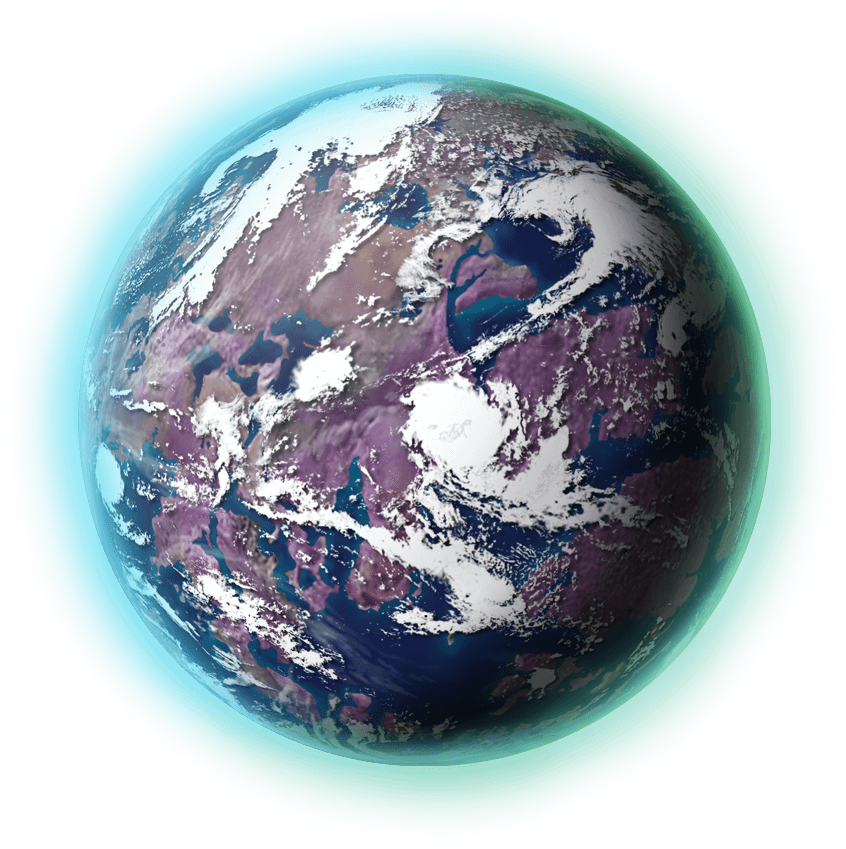

Veteris-42820 C

On the outskirts of a beautiful nebula sits a relatively commonplace star system. The K-type star, Veteris, coalesced from a wayward cloud of gas and dust around nine billion years ago along with its fleet of planets. Over the vast stretches of deep time, the nebula has birthed many such stars, and seen nearly as many die. However this one is far from ordinary, for within a rather exacting proximity range, a planet orbits with a high percentage of water. Within this habitable zone, the star's radiation is at just the right levels to allow this water to exist in its liquid state. This planet is known officially as Veteris-42820 C, but for the sake of brevity, we will shorten its full name to Veteris and refer to its star as its sun. With a constant source of energy in the form of ambient starlight, a large variety of complex chemicals as a substrate, and abundant liquid water on its surface, Veteris began to develop a peculiar physical anomaly... life.

Planet Data

| Age: | 8.1 billion years |

| Diameter: | 9,756 km |

| Mass: | 4.56 x 1024 kg |

| Orbital Period: | 241.3 days |

| Rotational Period: | 30.62 hours |

| Axial Tilt: | ~9.4° |

| Atmos. Density: | 1.4 atm |

| Gravity: | 5.9 m/s2 |

Veteris is quite old - about twice Earth’s age. It has been lucky to avoid major asteroid impacts, and the number of mass extinctions throughout its history have been minimal, and far less severe than in our own. This fact, combined with Veteris’ highly diverse geology and stable climate, means that many of the planet’s original biological genera are still in existence - albeit in highly evolved forms. Nearly devoid of such periodic disasters, Veteris is an example of extreme biodiversity. Most biomes here have species numbers on par with our Amazon rainforest, with many exceeding it. An enhanced number of species over time leads to greater chances for very specific niches within the environment, and this in turn leads to specialization and the forming of symbioses.

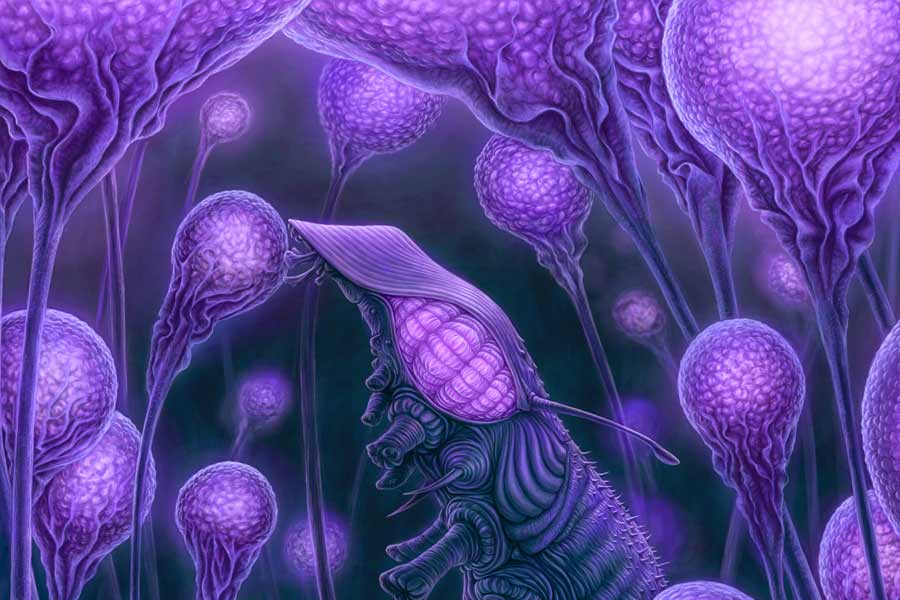

Veterian Biology

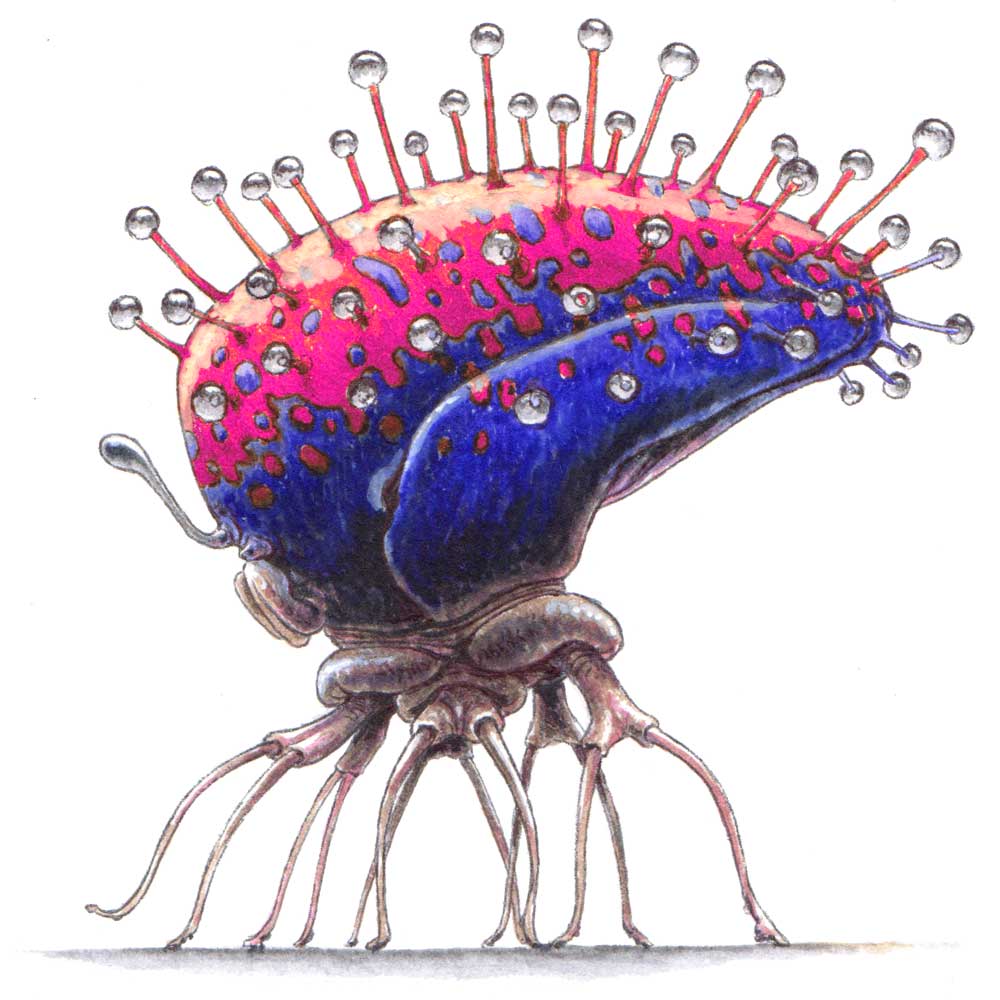

A common theme on Veteris is cooperation. In many instances, a given pair of species will trend away from an antagonistic relationship towards one that is mutually beneficial given enough time. That’s not to say that predation is rare—it’s certainly quite common. However, energy acquisition is more diversified here. For example, most creatures derive a certain percentage of their energy needs through photosynthesis. The level of autotrophism is inversely proportional to mobility. The more active the creature, the less of its energy needs are supplied by the sun. Additionally, there are organisms which vary this level of autotrophism over time due to ontogeny or environmental factors. This lessens the day-to-day pressure of finding large amounts of food, and allows for more interesting partnerships than just standard predation. The level of interdependence between creatures here is quite remarkable. Some species rely on each other for reproduction to such an extent that it is hard to distinguish between species and genders (ex: ‘Egg Chamber’). Others combine body plans to form “composite organisms” such as the Glass Colligatio, which are much more effective at surviving than the individuals would be separately.

Most large creatures here do not have significant endoskeletons or jointed appendages. Much like on Earth, life is thought to have begun in the sea, but the organisms which were the first to crawl out and dominate the land had tube legs. Partly due to the lesser gravity here, rigid internal structures such as bones were not necessary, and the evolution of reinforced hydraulic tubes was selected for. Many organisms share this common anatomical feature, with extreme variations in leg size, number, and arrangement. For large creatures, such as the Magnavindix and the Tripodal Plains runner, the legs are flexible, yet strong. Internal muscular cavities filled with fluid expand and contract to extend the legs. This is slightly less effective at achieving great speed than the jointed legs of say a cheetah or deer, but given the denser atmosphere and lower gravity on Veteris, such speeds would be extremely hard to attain anyways. To counter the greater air-resistance, many creatures have evolved aerodynamic outer surfaces and body shapes.

Another common trait among Veterian organisms is bioluminescence. Over half of all creatures here can produce light, and in places such as the Glow Forest and the Deep Sea, the number may be upwards of ninety percent. Emmitting light can serve many purposes, from warning predators to attracting a mate, and even camoflauge. To make use of this light, most creatures here have sophisticated eyes. The evolution of eyes is thought to have occurred at least seven independent times in Earth's history. This is very strong evidence that wherever life arises, the ability to detect light will be a universal trait. However, eyes on Veteris look quite different than many of Earth's creatures. Most ocular systems here consist of an outer transparent shell with separate, often moveable internal lenses. Some organisms have separate sets of eyes to detect light in different wavelenghts—often in the inrared or ultraviolet portion of the spectrum.

A world full of life

Biological processes arose spontaneously on Veteris. Perhaps life itself is simply an inevitable emergent property of matter under a certain set of conditions. Veterian life is the same type that we have on Earth—Carbon-based, using water as a medium. And much like earth-life, Veterians utilize a hereditary molecule, although one quite different than our DNA. This system of genetic inheritance is imperfect, leading to variation among populations of organisms. Based on these differences, creatures experience differential survival and reproduction, and thus evolution by natural selection. The phenomenon of evolution is one we expect to see emerging in tandem with living systems, and although it is responsible for culling a subset of creatures, it creates the magnificent spectacle of countless lifeforms we see around us. The unique conditions on Veteris have led to extreme speciation and diversity. In this planetary greenhouse of life, there are far more lifeforms than can be described within the bounds of this project. Come along on this journey as we visit a few of the many inhabitants of this wondrous and exotic world.